Should London's West End Make Money, or Make Room?

Long-running shows are taking up space but maybe that’s not such a bad thing

This was originally posted on Medium, and since it did shockingly well there, it seemed like a good candidate to include here on Art+London.

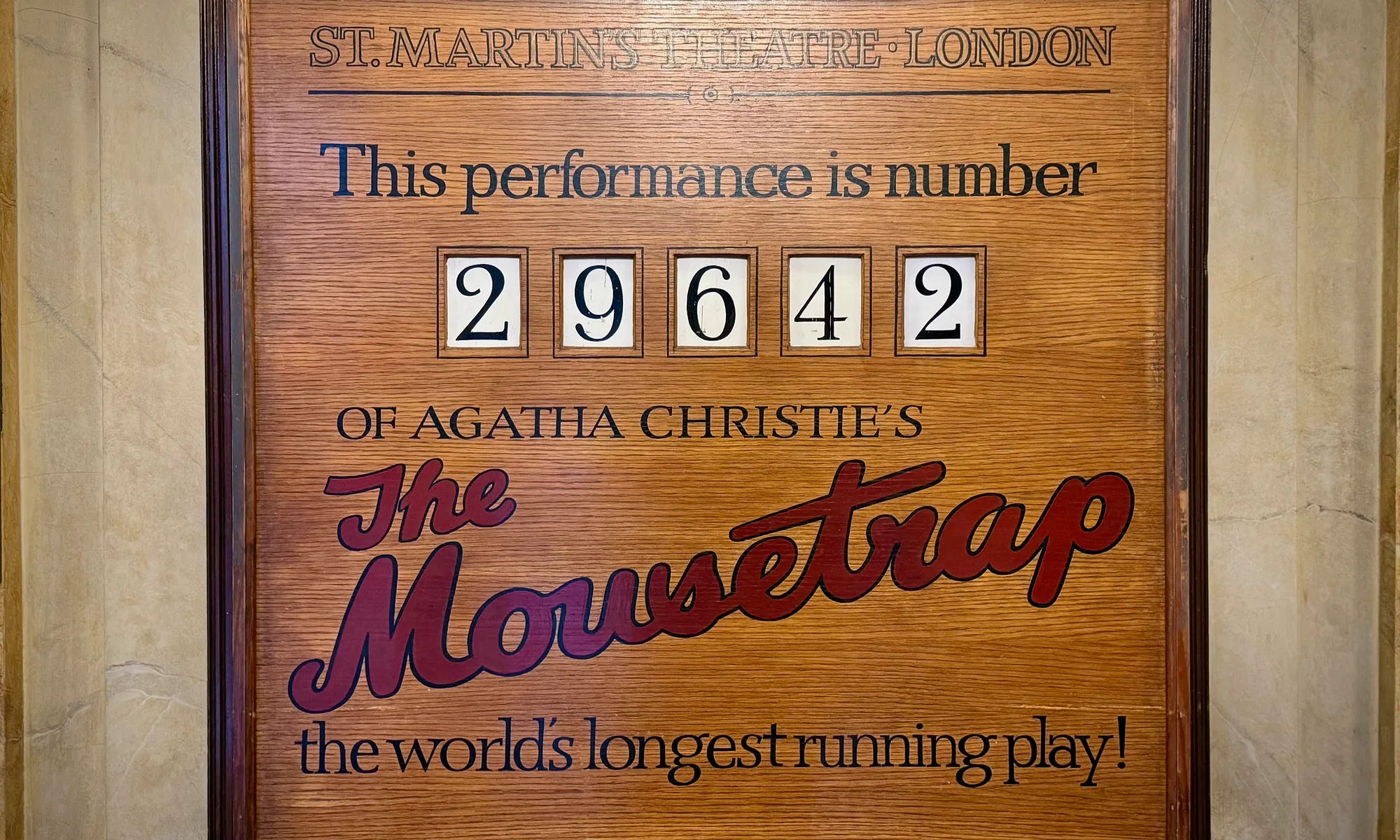

In the upstairs bar at St Martin’s Theatre, I wasn’t drinking — I was reading. The walls are hung with an admirable number of framed newspaper comics, each one poking fun at the long run of Agatha Christie’s The Mousetrap. What makes it all especially quaint is that some of the comics were drawn while the play was still in its sixth year.

Today, The Mousetrap has been running for roughly seventy-one.

I watched performance number 29,642, but regardless of whether you are looking at years or performance numbers, it is the longest running show on the West End — far ahead of the thirty-eight-year run of its closest rival, Les Misérables.

Looking at those vintage comics, I was struck by the fact that The Mousetrapmight stay open forever.

There are currently eight theatres in the West End that have been running their respective shows for over a decade. And I began to wonder why some productions seem to go on for years while others wither after just a few weeks.

How does something like Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd flop after only four months in its first run, while Andrew Lloyd Webber’s plotless Cats ran for twenty-one years?

Once I began looking into it, the answer was both complicated and simple. Unsurprisingly, it mostly comes down to money.

Now, I want to be clear, I have no desire to see The Mousetrap snap shut.

Who can imagine London without The Mousetrap? If Christie’s play came to an end, it would be like the ravens leaving the Tower. It has reigned in the West End longer than Queen Elizabeth II was on the throne. It is older than the McDonald’s franchise. Older than colour television on the BBC.

The Mousetrap is an institution. And any piece of successful theatre is a win in my books.

Yet, at the same time, a voice in the back of my mind asks the terrible question: How many other plays might have been staged in St Martin’s Theatre if The Mousetrap had run for a perfectly respectable six months?

Over the past seventy years, there could have been 140 more plays on that stage with a generous run of six months each. And if those runs were shorter (which they typically are) the number would double.

What overlooked piece of writing might have become the next Waiting for Godot? The next Birthday Party? Surely, even if some of these hypothetical St Martin’s shows were revivals, there would have been room for new work.

Right?

Fringe Benefits

I’m a champion of small theatre.

As an audio-drama writer and a playwright who’s had exactly one shoestring production of my work in community theatre, supporting small theatre is a kind of karmic exercise. Nevertheless, I actively seek out small productions because sometimes — when all the stars align — they can be the most intimate and powerful shows you’ll ever see.

And besides, how else can we know what kind of fresh talent we might be missing out on?

In my university days, I fell in love with the Toronto Fringe Festival. And since then, I’ve been to as many theatre festivals as possible — the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, the Vault Festival (now-heartbreakingly defunct), the Camden Fringe. The list goes on.

Events like these offer a stage to the kind of plays that may never make it to the West End because they lack the funding and connections.

But, some do make it. And a few of the productions that have succeeded are prestigious: Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead had its debut at the Edinburgh Fringe, as did Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s show Fleabag and the West-End musical juggernaut, Six.

So, small shows can become big shows. And small names can become household names. But small venues and theatre festivals will always be the indie scene to commercial theatre’s pop-star status.

After all, it’s in the name: Commercial theatre exists to make money.

To me, it seemed obvious that big, shiny musicals and multi-million-pound stage productions were stealing the spotlight, space, and money from smaller productions. So, I decided to look into just how the West End functions, ready to point the finger at the greedy men in suits hoovering up the cash.

But the West End is not quite the vampire I imagined it to be.

It’s a Rich Man’s World

Saying that producing a show in the West End is expensive doesn’t really do the costs justice. West End shows are not merely expensive — they are eye-wateringly, astronomically expensive.

The start-up costs — that is, the funds required to simply hire everyone, rehearse, build sets and advertise before the actual production — begin in the hundreds of thousands of pounds. That’s for the very smallest of plays — a four-to-six-player performance with a handful of musicians and small technical crew.

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, with its cast and crew of hundreds, demolished all the records with a production cost of £48 million, making it the most expensive non-musical ever to grace a stage.

For musicals, start-up costs average £3.5 million, although there are exceptions here as well. Because Six found its feet in the Edinburgh Festival Fringe before moving to the West End, its small cast and simple set incurred a startup cost of ‘only’ £500,000.

But most shows require much, much more.

It’s little wonder that in theatre circles, they call their investors ‘angels.’Securing that kind of funding for a show that could simply flop seems like an act of pure faith.

Nor do the costs end there. Once you are ready to stage the show, there are weekly and monthly expenses: The venue’s rent, the ‘dark costs’ (up to £150,000 just to maintain and repair the building itself), the utility bills, wages for everyone involved — from actors and directors to the front-of-house staff, cleaners, agents, lawyers, technicians and marketing.

And let’s not forget the taxes — but we’ll come back to those.

What this means is that even after that first £3.5 million is raised, an average West End show needs to make approximately £335,000 per week just to break even.

To break even.

If a weekly £350,000 is the break-even point, producers need to charge a bit extra on tickets so the show can make a profit and begin to pay back its investors. They also have to include a financial cushion for the seats that go unsold, because no show will be at peak capacity every day.

You can consult Richard Howle’s excellent breakdown if you want to really dig into the numbers. But simply put, this means the average profitable price of a ticket to a West End musical is £50, and the show will need to run for around fourteen weeks before it can even begin to pay back its start-up costs.

Now, £50 sounds like a great price for a seat in the stalls to see Hamilton, but sadly, all seats are not created equal. No one is going to pay £50 to sit at in the back of the circle, where half the stage is eclipsed by the upper-circle balcony. No one wants to pay £50 to sit behind a pillar or to have their view of the stage blocked by the balcony railing.

There are, however, people willing and able to pay much more than £50 to sit in the best seats in the house — the oft-reviled ‘premium’ tickets. And so, accordingly, the best seats are adjusted up in price. And the worst seats are reduced.

This surprised me. In fact, the closer I looked at Howle’s article, and other similar pieces, the more it seemed like ticket prices were unexpectedly egalitarian — spreading out the prodigious production costs so that audience members who can afford to pay more subsidise seats for those who cannot.

The view may not be so good for those of us in the cheap seats, but it’s the same story in music and sports.

‘Where did we go right?’

There is often the perception — particularly in fiscally conservative circles — that the arts are a drain on government money. The argument goes that arts spending is the great black hole from which nothing tangible or useful ever returns. As such, arts funding is inevitably the first item on the chopping block when the economy is down.

The West End, however, is an entirely different animal.

In fact, according to Nica Burns — producer of the musical Everybody’s Talking About Jamie — there have been fewer flops than ever in recent years because the industry has become better at making hits.

The longer-running shows are proof that the mix of spectacle and flexible ticket pricing works. And the longer a show runs, the more money it stands to make.

While that may have the stink of a slick record producer ‘polishing’ his newly acquired indie band, there is one important thing about money in the West End. Everybody gets some. Especially the government. And that’s a good thing.

Let’s head into the maths one last time: In 2022, the Society of London Theatre estimated the total box-office takings of the West End at £892,896,521. If we go with the accepted 13-percent profit margin on each ticket, that’s £116 million pounds of profit spread between its various productions.

That’s not a small industry, and much of the profit will return back to theatre and the arts in one way or another.

More importantly, that’s £178.6 million in VAT that goes straight to the treasury. Theatre is a tax gold mine, which explains why, during Covid, the otherwise arts-hostile Tory government decided to offer tax incentives to keep theatres alive through lockdown. Then, two years later, they extended that program— just to make sure that this billion-pound industry kept the taps open.

The Angels’ Share

So, how does this help small theatre?

If you’re being cynical, it doesn’t. Not directly. Once you step out of the West End, you’re mostly back to productions looking for grants just to stay alive, and small community theatres asking for patronage and memberships, and hoping for volunteers to staff them.

And when you look at the ludicrous costs involved in running a show in theatreland, it’s clear that shorter runs would not result in more stage-time for upstart productions. It would just mean fewer chances for big productions to pay back their startup costs, and less political clout for theatre in general.

When I started down this rabbit-hole of the business-and-numbers side of the West End, I expected to dig up greedy producers and giant corporations dumping ticket-revenue into their mega-yachts. And I have no doubt that there are names in the industry who lack for very little, but without successful producers and plenty of wealthy ‘angels,’ where would we be?

The producer Nica Burns is also the co-owner of six West End theatres. She has produced over 100 plays and musicals, is responsible for thousands of paycheques to industry creatives and technicians, and is an outspoken voice for arts funding.

Burns got her start in the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, now she creates jobs for hundreds of people in the arts world.

If I’m beginning to sound like a cheerleader for Capitalism, I’m not. For every story like Nica Burns’, there are a thousand failures and ten-thousand struggling creatives. Capitalism makes sure of it. And the perception that the arts are a frivolity persists among people in power, making it a struggle for small theatres to even survive.

But I am, to a degree, a pragmatist and a proponent of theatre giving back to its own. If the arts has to play the game, it seems the West End is an exceptionally good player. And it’s a player that cares: Its producers can quote The Producers, its fat-cats have seen Cats, and its profits are more likely to find their way to South Pacific than the Cayman Islands.

The benefit to smaller theatre is that the West End still gets its actors, writers and directors from all those shows on the fringes. And while it is reductive to look at regional theatre as if it were nothing but an incubator for the West End, a healthy West End is more help than hindrance to the arts in general.

If theatre is an economy, the West End is its financial district. But instead of hedge funds and investment banking, the West End gives us Two Strangers (Carry a Cake Across New York), Six, and Standing at the Sky’s Edge.

And in this new and surprisingly optimistic theatre economy, producers are willing to take a few risks. And that may usher in a new batch of daring British shows.

Maybe one day, those shows will give The Mousetrap a run for its money. ◼︎